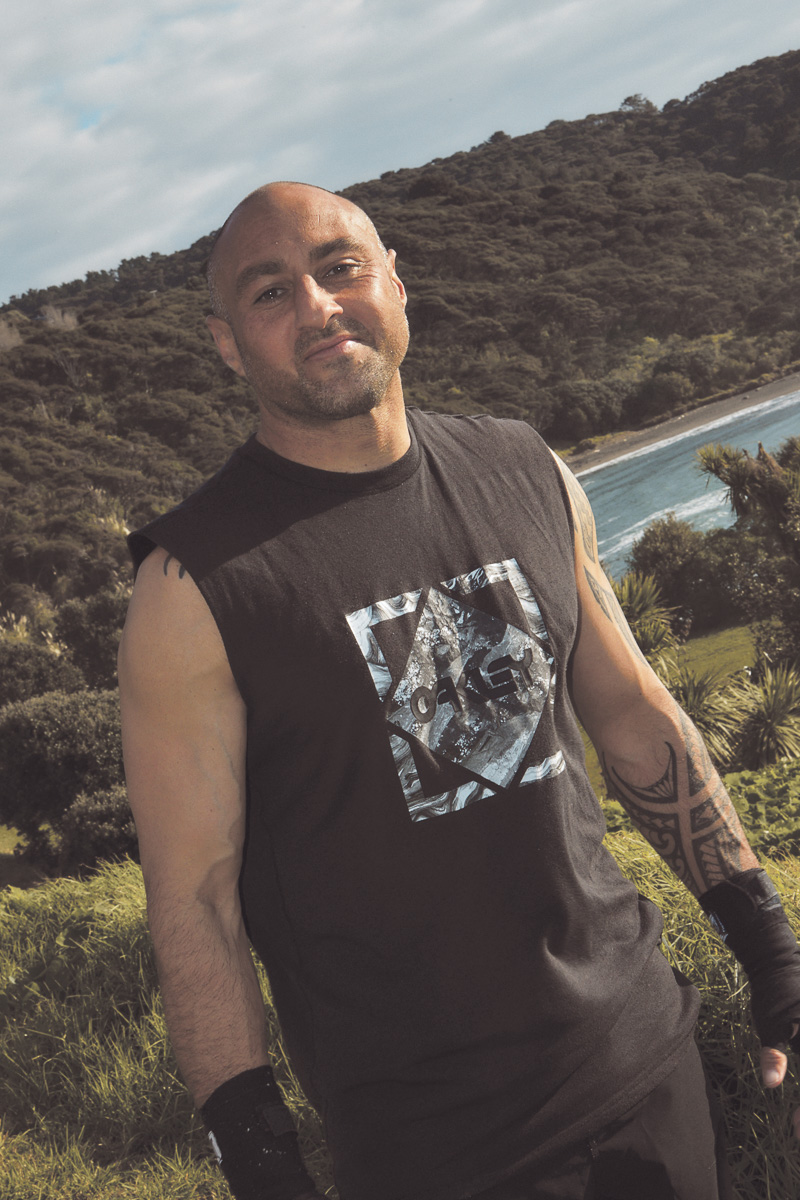

Johnny Rickard is a familiar, smiling face known to many around Whāingaroa as the man behind The Refinery, the martial arts dojo down at the kōkiri. The Refinery is a branch of the Whāingaroa Kyokushin Karate Club which has been run since 1994 by Johnny’s father, Pablo. We caught up to chat mental health, martial arts, and the strategies he uses to maintain balance in his life.

What is your relationship like with your mental health?

My mentality is only one aspect of my relationship with my hauora. Balance, for me, is having awareness of each of the compartments of Te Whare Tapa Whā. You’ve got taha tinana (physical), taha whānau (social), taha hinengaro (mental) and taha wairua (spiritual and emotional). If you can be aware of how each one of those things needs adjusting then it’s going to greatly enhance your ability to achieve balance. My relationship with my mental health is basically engineered through the martial arts. I was taught karate from a young age by my father, 5th Dan Blackbelt, Pablo Rickard. For me, it’s the concept that martial arts gives you around dealing with conflict. To be ready for conflict you have to be balanced and continually training. It’s like with your mental health; when you have a downslide, if you’re ready for that challenge, you ain’t gotta get ready. All the tools that you need to come up with the solution are already there within your daily life. I can’t really attest to too much more than that. I don’t have all the answers; I don’t think anyone ever has all the answers. Just like martial arts, we’re all different shapes and sizes, we all come from different backgrounds and we all need different tools to meet life’s challenges.

Is your mental health something you consider every day?

I spent most of my life training as a fighter. It was a large part of my life right up until my mid to late 30s. When I stopped fighting, it was a really difficult time for me and I wasn’t motivated to train. Then I realised that training is a major component of my life, regardless of whether I’m fighting or not. The goal for me wasn’t to fight anymore, it was to be balanced. Now it’s something I do daily. I’m up pretty much every morning at 5. If I’m not training, I’m out walking or surfing or out on the land watching the sun rise. I’m a firm believer in getting up and getting amongst it.

How has running the dojo impacted your sense of self?

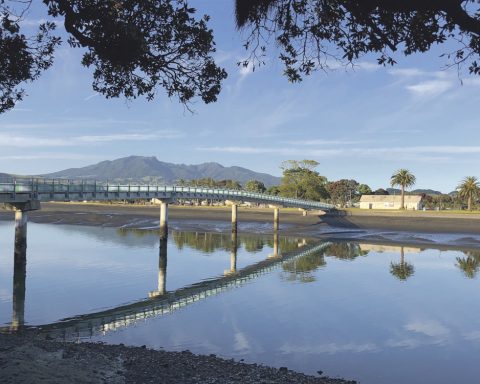

It has helped my taha wairua. I went through a large part of my life where I wasn’t sharing my knowledge and my love for activity because I was training myself. I’ve always been a school teacher and loved the gift of connection. When I couldn’t fight anymore, it became about seeing that there was a need for togetherness in our community. That fills my cup spiritually because I know well enough that I could be doing something else, somewhere else for lots more money but I wouldn’t live the lifestyle that I’m living here. People always say to me ‘bro you’re always happy, you’re always vibing’ but after the pandemic, I firmly took responsibility to be more open with myself and others. I think the dojo and martial arts is the vehicle I use to give that to people. My goal is to get people there and get them to engage with themselves. Whatever they need to do to obtain their own balance, whether it’s to be social with people, to be physical with themselves or to engage with the land down there and find some kind of calmness and peace. That’s why I named it The Refinery; it’s a place where you refine yourself. You gain things or let go of things and refine where you need that balance.

At your lowest point, what has kept you going?

I’ve been through some shitty times in my life where I lost my ability to maintain my balance. The key things that helped me out were my whānau and friends and being able to reinsert myself into an environment where I could find balance. Tuning in to those basic needs; make sure I get enough sleep and enough good kai, make sure I don’t work too much, make sure that as much as I look after others, I give myself some time. It’s quite funny because when I’m at home, it’s my little haven. I live by myself and I almost wish people could see me in that environment cause they’d be like, ‘Oh? You can actually chill.’ That is how I look after my taha wairua and my taha hinengaro. Running around and exercising, I’ve been doing that my whole life. I look after myself the most when I rest.

What are some of the lessons that you’ve learned?

Don’t be your own worst enemy. Have confidence in yourself and your abilities. One thing I wished I realised earlier in life is that I was capable of many things, but I didn’t believe in myself. I always had this inner fear of disappointing people or failing or getting hurt. Our time here on earth is finite. If you really want to do something, then do it. What’s the worst thing that can happen? You have to hit the drawing board again and rethink things. Three years ago I was weighing up whether to run the dojo or not in the middle of a whole bunch of life challenges. Here I am two and half years later and everything has worked out. It’s like fighting, you give it a stab. Worst case scenario, you get knocked on your ass. You get back up, that’s the most important thing. Bruce Lee always said ‘don’t waste time because time is what your life is made up of.’

What are some of the tools in your toolbox?

Every day that I go to the dojo I make reference to the Whare Tapa Whā and I try to accommodate the individual needs of each one of those four components to maintain balance. I like it at the dojo when there’s no one there. I often look out to the land, I look out to the sea, I don’t have to engage with anyone, and I think to myself, what do I need today? Sometimes we don’t know what we need but if you’re in a quiet space and you can engage with calmness and nature, the answer will come to you. I do understand we all have responsibilities but if you commit to having that check in space then you will fit whatever it is you need to around that. It’s a learned strategy. I’m lucky to have the dojo, that stuff is clear and present there. There’s the physicality of the bags right there, I’ve got my whānau right there, I’ve got the environment right there. That’s the space where I can integrate that learned strategy of checking in. I think I’m truly fortunate and also honoured to be able to engage with that on my own measure.