Lucy Haru feels right at home at the Raglan Community House.

The day we meet Lucy is working on a jigsaw to make sure all the pieces are there before it goes up for sale at the op shop.

“People ask me why don’t you just count them but I like to do them. It’s good for my brain,” she laughs.

Community house manager Mike Rarere reckons Lucy also provides a calming influence and outstanding mediation skills.

“For me, it’s awesome having another pair of eyes and ears on situations that can be quite challenging at times,’ he says.

When she’s there, Lucy is under the watchful gaze of her kuia Herepo Rongo, whose portrait hangs in the community house’s lounge.

Herepo was the last woman with moko kauae in the Poihakena community in her lifetime. She fought alongside Tuaiwa Hautai ‘Eva’ Rickard and others to have their ancestral land returned after it had been taken for a wartime airstrip and then turned into a golf course by the council.

Lucy’s not just the puzzle lady; she’s is the go-to for ukulele lessons, works parttime as a special needs teacher at Raglan Area School and more recently she’s hit the radio waves teaching conversational Māori at the Kupu Café on Fridays from 11.30am-12.30pm.

The radio show morphed out of the first iteration of the Kupu Café at the community house. When Covid made gatherings a bit complicated, Whaea Lucy was still keen on sharing te reo with the community.

“I thought there had to be another way and then I met Yvonne Scully, and she said – why don’t you go on the radio.”

It all made perfect sense, no worries about masks and scanning; Lucy could continue to share her reo and tikanga knowledge in the safety of the radio studio.

Lucy’s the first one to admit she’s not tech savvy and Yvonne provided technical support until she went overseas and another radio volunteer Sammy took over.

“I don’t know how to do the logistics of the radio so Sammy’s my techno-funk,” Lucy laughs.

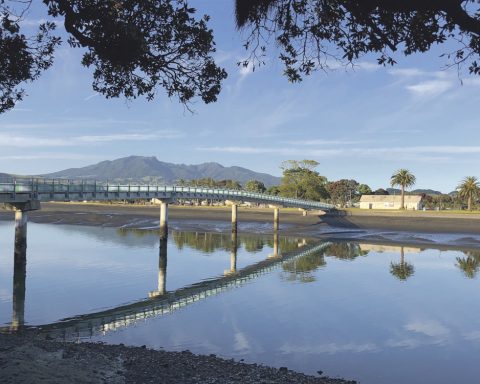

Lucy lives in her grandmother Herepo’s house overlooking Te Kōpua – home to the Kokiri Centre and the whānau camping ground.

“Because my mother had looked after her mum then I came back to look after my mum (Waiapu Isobel Haru) – kind of runs in the family,” Lucy says.

When the golf course land was finally returned to the iwi in 1983, Lucy was living in Auckland.

Having grown up on a farm in Te Akau, you couldn’t get any more remote and Lucy headed for the city in search of work.

Living in Otara, Lucy progressed from factory jobs to working for the Manukau Technical Institute providing horticultural training to young people.

It was a natural transition for the country girl.

“Being a farmer’s daughter, it was like second nature to me. Even though I was living in the city I was still working the land to grow vegetables and flowers and stuff.”

The scheme was called the Training Access Programme (TAP); it was a time when rising unemployment and inflation were hitting New Zealand hard.

Many of the young people Lucy worked with were directly impacted by economic hardship and the programmes were created to provide a pathway to employment.

“I’d see what it did to these young kids getting in trouble. Sometimes they’d come in to work and they would be in lala land and I’d say – I think you need to go home. So, I’d get them a taxi and tell them – go home and sleep it off – and then they’d come back to work the next day.”

Working for the programme provided Lucy with her first trip overseas. It was 1984 and she was invited to attend an indigenous hui in India.

“They got in touch with me because they had a lot of office workers and they wanted someone who was grassroots.”

To prepare for the trip, Lucy ate rice for one whole month; she wanted to experience the real India.

“I knew I was going to a poor country and I knew that rice was a staple diet. I didn’t want to go there and be like the office workers and have these flash meals.”

When she was asked to deliver a report to a church group once she was back home, she took them on an excursion to the rubbish dump.

“The church leaders came to me afterwards and said – that was a bit off. And I said – you wanted a report, you wanted to know what it was like. Now, you have a very clear idea of what it looks like and what it smells like.”

Lucy had caught the travel bug. Wanting a contrast to India, Lucy travelled to Japan in the late 1980s and she returned to a much-changed India in 2015.

The eight years Lucy spent working at the TAP made her realise the importance of early intervention in the lives of vulnerable young people and she trained to be an early childhood educator in 1995.

“I decided if I could catch them earlier before they go off the rails then I would have hopefully broken the cycle.”

She had moved to Raglan in 1990 to look after her mum – to be back on her mother’s whenua – and to learn the tikanga and reo.

She worked at the Raglan Kindergarten for many years, and did teacher relief work around the Waikato district.

The 66-year-old might be at retirement age but she’s definitely not ready to stop working.

Whether it be teaching the ukulele chords to beginners, inspiring te reo learners or getting stuck into the jigsaws at the community house, she’s driven by the desire to help others.

“In a very small, under the radar way I’m helping people out where I can, when I can, how I can.”

By Janine Jackson