Sands of time: Continuing our occasional history series, we look back to Whaingaroa a century ago – 1918.

A century ago, the Great War continued most of the year and troops were still being enlisted until shortly before the German Armistice in November 1918. However, each armistice was celebrated, starting with the surrender of Bulgaria at the end of September. Does anyone know which was being celebrated in the photo above of the Harbour View Hotel?

Of the 20 soldiers from Whaingaroa who died in the 4 years of war, eight died in 1918, though only three on active service with the rest dying from injuries or disease.

The last three were all farmers and only arrived in Europe in 1917 or 1918. They died in a small area of northern France, within three months of the final armistice.

Gordon Ferriman moved to Puketutu, on the Waitetuna River, just beyond Te Uku, with his family about 1910. He left on June 5, 1918, arrived at Liverpool on July 31, and was 21 years old when he was killed on October 24 at Le Mesnil. Another son, Joe, also went to war, but returned to the farm Puketutu.

Patrick Phelan was one of 8,530 names drawn in the May 1917 ballot for military service. He’d recently married and started farming at Lake Disappear, beside the Kawhia road. At a Military Appeal Board in June he said his two brothers had gone to the front, one being recently killed, which left no one to run his farm. The Board was not sympathetic. They suggested someone be put in charge and gave him two months to arrange it. On December 31, 1917 he sailed from Wellington, reaching Glasgow on February 25, 1918. In May 1918, he was wounded and in hospital. He died, aged 34, at the start of the Second Battle of Le Cateau (October 8-12; the first battle was in 1914), where 536 died. The only brother to survive the war was Francis.

Henry Lionel Coate worked on a family farm at the back of the harbour. He left Trentham Camp on April 26, 1917, arriving at Plymouth on July 19, and being killed just over a year later, aged 31, on August 26 at Bapaume.

The Military Appeal Board was also unsympathetic when Alf Galvan appealed. He said Te Akau farmers depended on his ferry to get mail and supplies and he was the only one who’d applied to be ferryman. The Board said his brother should study for an engine-driver’s certificate and become ferryman, giving Alf until May 9, 1918, though he didn’t go to Featherston Camp until October. Thus he was in the camp when the influenza epidemic was at its height. His mother, Sarah Ann, travelled from Raglan to see him when he was ill, but she too sickened on her way home. George Blackett had retired as Raglan school headmaster in 1917 and, when the epidemic struck in October to November 1918, his wife, a nurse, transformed the Stewart St school into a 34-bed hospital. Mrs Galvan died there on October 22. Her son died at Featherston on November 14. Andrew Hume, a Kauroa farmer, and Francis Bulford, son of Raglan’s first policeman, also died in the epidemic.

Another 1918 death was J. W. Ellis, who was Mayor of Hamilton, but had been a trader at Motakotako, just north of Aotea Harbour, in the 1870s. He later went on to form the timber company, Ellis & Burnand, which was, much more recently, merged into Placemakers.

When a kiwi was killed by a car near Te Mata, the news report said they would soon be like the moa – a thing of the past. However, a Bryant Reserve management plan as late as 1981 did mention kiwi.

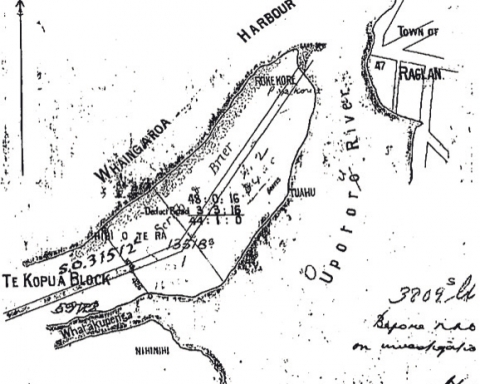

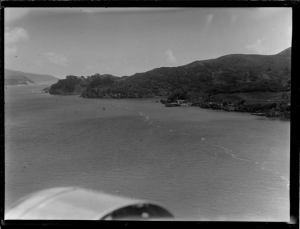

1918 wasn’t just a year of death and destruction. Te Akau gained a new phone cable across the harbour and a new wharf and goods shed. Road transport was increasing, but much still travelled by water and the steamer from Onehunga called weekly, except when disrupted by the flu epidemic.

The Wallis St causeway across Aro Aro was almost complete. However, the Waikato Times thought an opportunity was missed for the sake of £56. That was the amount the council wouldn’t agree to pay for a floodgate to create what the paper described as, “an ideal salt water lake in which bathing could be safely indulged in”, by converting, “what is now an unsightly mud flat at low water into a permanent and beautiful lake”. In the 1960s a flood gate was installed to keep the tides out, though a 1978 report questioned whether it had been given official approval.

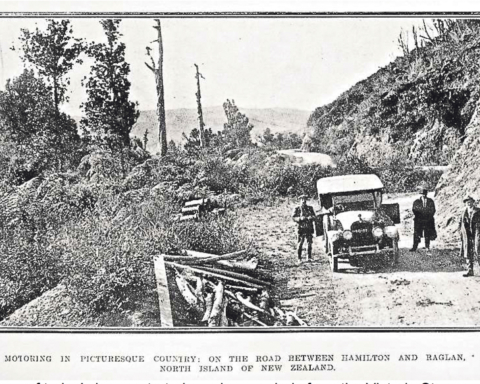

Roads continued to get gravel spread over the mud, with loans taken for Creek St (now Wainui Rd), to Opotoru bridge, and for a further 8 miles of the main road.

In 1918 a new Methodist manse was built. It lasted until 1989.

So 1918 hasn’t left a great deal other than the Wallis St causeway, though the war memorial followed in 1922 and gravel laying on the main road allowed the last patch of mud to be covered in 1921.

John Lawson