Cynthia Tucker was set to be at Raglan’s Anzac Day service at the cenotaph today, as always.

“I go to every one,” she told the Chronicle. Except nowadays she takes the grandchildren along too.

Raised with two sisters on an isolated Ruapuke farm but now living in Gilmour St, Cynthia attends the service to remember her late father Rex Tucker, a trooper in New Zealand’s 18th Armoured Regiment.

Every year the now 64 year old reminds her family how lucky we are to live in this country. “We’ve got to remember them (the Anzacs),” she says. “They sacrificed a lot.”

Cynthia and older sister Pauline – who also lives in Raglan, on the way out to Ngarunui beach – remember their father with pride and shared this week the way his two years as a young man serving in Italy, Egypt and the top of Africa affected him and shaped their family life.

They recall how Anzac Day was one of the most important days of the year for Rex, certainly the only time this dyed-in-the-wool farmer dressed up and put on a tie. “All the farmers marched with such pride,” says Cynthia. “And they never missed the parade, even if they were sick.”

Rex may have always made the parade – or its forerunner, the church service in Raglan Town Hall right after World War II – but wouldn’t ever wear his service medals, Cynthia reveals.

Her father didn’t go to war for the medals. “He said he went because it was the right thing to do.”

Even more precious to Rex than his medals were the two ‘dog tags’ he wore. The tags – so named because of their resemblance to those on dog collars – were stamped with soldiers’ regimental details, one to be left on casualties at all times for identification purposes.

“But Dad came back with both,” says Cynthia sombrely.

Almost as important as Anzac Day for Rex were the reunions he had with comrades for the rest of his life, the sisters agree. That’s where they gleaned more of an insight.

They remember traipsing as far north as Kamo, Whangarei, as a family to visit their father’s wartime mates and – within the district – attending regular reunion picnics on Wright’s farm just east of Raglan.

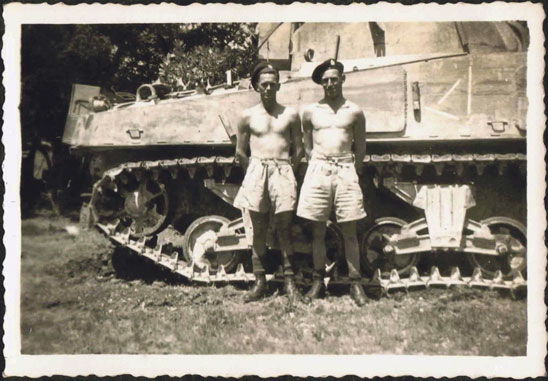

While Rex was both a flamethrower and driver in the tank corps, Pauline explains, local soldier Whit Wright was the sergeant. “They had all lived together and had a lot of fun (in downtime) but the fighting was traumatic,” she says.

Other locals like Reg White and Sam Kereopa in the Maori Battalion – for which the 18th Battalion provided armoured support – became like family to their Dad and in turn to them.

“The bond was there right to the end of their lives,” Cynthia says of these brothers in arms.

They’d all gone to war from Ruapuke and Te Mata, the pair recall, thinking of it as a big adventure.

But Rex never talked to them personally about his experiences there until later in life. “And Mum said not to talk about it,” Cynthia recalls.

They know however he suffered from shrapnel injuries in the back of his neck, and from nightmares soon after the war.

In one incident involving shrapnel, Cynthia recalls, their father was apparently slumped but struggled to sit up when he overheard a directive to “throw him over”. That story may have been embellished, she suggests now, but all the same it was a “ruthless, shocking world”.

Another near-miss came after he and comrades fled their stalled tank for safety back in the trenches, only to be told to return to get their maps before the enemy did. Apparently bullets came from every direction and Rex was relieved when the stalled tank started and he could make his escape.

The sisters remember too how their father used to take them up the back of the farm to be on the lookout for Japanese forces, as rumours were circulating at the time of an imminent invasion and landing in Ruapuke.

Edith Symes