It’s widely acknowledged that discharging a flare incorrectly, at the wrong time or in the wrong place could deem the act entirely hopeless and quite dangerous.

When using a flare as a maritime distress signal, the user has to be physically competent in its discharge in any situation and have strong confidence that it will work.

I’ve worked with many recreational mariners who proudly attest to keeping flares on their vessel, and it is extremely positive that the flare continues to be valued as a distress and signalling device. However, storing them in plastic bags with condensation, not checking expiry dates and not knowing how to use a flare correctly cancels out every good intention.

First-hand experience tells me that these types of pyrotechnics can be compromised by moisture (beyond the instruction label curling off) and that they can fail to fire if used past their expiry date.

Discharging a flare isn’t necessarily easy either. There is some kickback that can give the novice user a fright – enough to let it go overboard – and the casing on hand-held devices heats up enough to cause severe burns.

Factor in vessel instability and the challenge of staying upright, and we must seriously consider that using a flare requires sufficient mock rehearsal to ensure that if required it will be discharged effectively and safely.

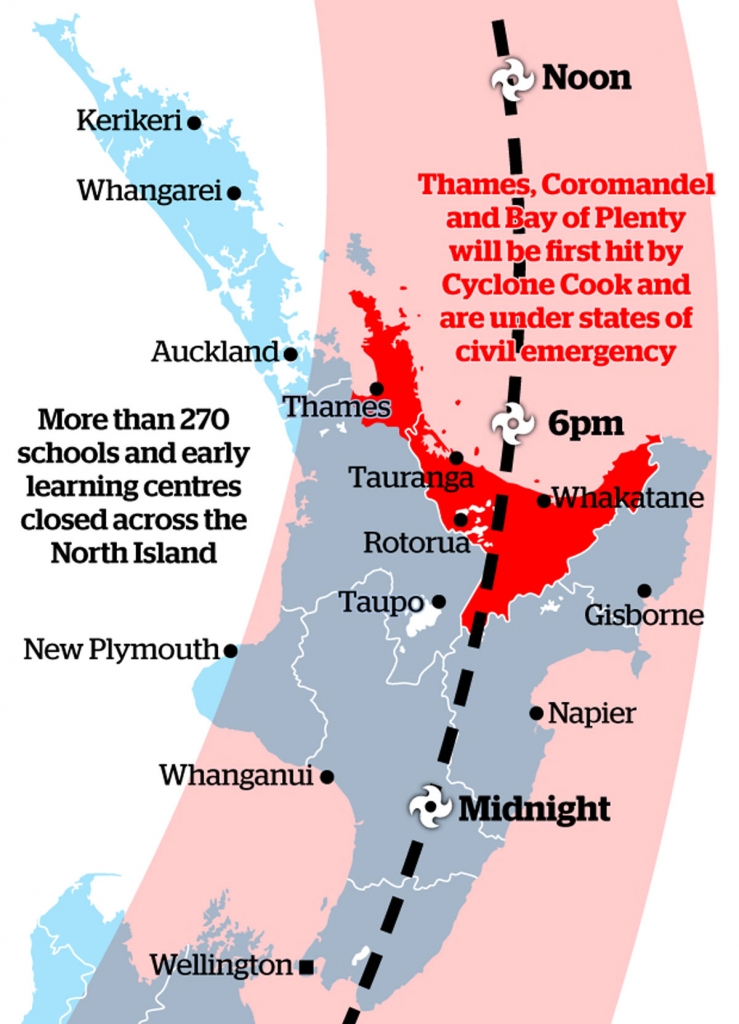

One such example was highlighted during a recent maritime rescue. In the early stages of a nasty sub-tropical storm, I was tasked with a crew to retrieve a 5.2-metre aluminium vessel with steering failure and two people on board. The 1.5m sea was confused, cloud was low and visibility was reduced to approximately 200m. A 30-35 knot offshore wind was blowing, gusting 50 knots at times. Between the wind and turning ebb spring tide, the stricken vessel travelled at least 2.5 nautical miles offshore from their initial distress position in just under 40 minutes.

Spotting the vessel was a challenge. However, VHF communication was clear and consistent. Good local knowledge from the skipper supported us to establish that we were close by. Air search support was out of the question considering the poor visibility, so the skipper of the distressed vessel was asked if he had any flares on board. It was anticipated that if he did, he would be able to use them. Fortuitously, and in minutes, we set eyes on the tiny grey cork just before the need to light a flare arose.

Safely on-board the Gallagher Rescue, the vessel’s skipper suggested he and his son didn’t have long before being swamped or tossed overboard. Considering the physical and mental exertion of holding on for dear life in such conditions, the request to discharge a flare may have been asking the impossible. The move would have required someone to enter the cuddy to retrieve, open the container, read the instructions and keep upright long enough to set off.

The skipper admitted he couldn’t manage a crouch to grab his mobile phone, which if he’d had it switched on may also have supported position accuracy. Furthermore, our request could have placed the skipper and his son at greater risk by assuming their flares were accessible, functional and that the skipper was fluent in their use.

Like any piece of equipment, flares have advantages and limitations. From a marine SAR perspective, I consider them invaluable for situations as described – but only if it does not increase the risk to people and their craft.

If you carry them, check them as frequently as you would every other piece of equipment on your vessel. Assess each device for integrity and always know where your flare kit is stored. Tell passengers the location of all safety equipment every time you set to sea, and dry run the flare discharge procedure regularly.

The more you prepare, the greater your confidence if you’re ever caught out.

Raglan Volunteer Coastguard can take expired flares for suitable disposal. Note, it is a criminal offence to discharge flares other than in a maritime distress or emergency. For further information, please email Viv viv.regnier@boatingeducation.org.nz